Disclaimer

I should probably start this blog with a disclaimer. I have no doubts that those who served with me in Sarajevo will have a multitude of similar stories about their service. They served in and around what was once a beautiful, cosmopolitan city. They will also have seen and experienced things over and above those that I’ll talk about. I know for a fact that one of those in our team volunteered to ride as the top gunner. He was shelled frequently during the infantry’s regular trips over Mount Igman. They did this to bring supplies for the British Forces into the city.

Similarly, several others experienced the war firsthand. They were at our sub-units at Sarajevo airport. Some were at our frontline detachments like Sierra Oscar and the Old Fort. I’m fairly certain there is a whole book of witty anecdotes to share! This, though, is just an opportunity for me to tell my story, to share my music as it were.

I should also note that I can’t recall everything that took place (it was 29 years ago and although I started with every intention of keeping a diary, this was only partially successful and while I remember some things as clear as if it was yesterday, others are more, ahem, rusted with age!). I will try to recount the main events as I recall them.

While 29 years ago doesn’t sound much, the Walkman I took to Sarajevo with me played cassettes. That puts time into perspective! I was only in Sarajevo for four months. I can’t claim to have seen the true horror of this war. The civilians who lived there had to endure it for far longer than I did. I’m sure that it was a living hell for them.

It was, though, four months that showed me that the inhumanity of mankind is often simmering just beneath the surface. And religion is often used as an excuse to exercise that inhumanity. It was also a time that showed how human kindness can shine through. Without doubt, humour is often the thing that sees people through such difficult times. In military circles that is certainly the case at any rate. I hope that this blog will bring out all three of those aspects.

During those four months from May to September 1995, some of the most intense fighting took place in and around Sarajevo. It was a time of almost total inaction from the United Nations that led to NATO stepping in to prevent any further atrocities. Several years too late for the inhabitants of the Former Yugoslavia, it at least brought open hostilities to an end. I suspect the country’s inhabitants still wear the scars, nonetheless. Some of those who served there from a multitude of countries will likely feel the same.

Introduction

It is said that there is a story in all of us. This is definitely the case for anyone who has ever served in the Armed Forces. Benjamin Disraeli once said “Most people die with their music still locked inside them”. These are sage words. They inspired me to start writing my own blog. I wanted to get the “music” out of my head so that it could be shared with others. Whether they had the desire for it to be shared in the first place is another matter altogether. Once the music is out of my head, it’s a choice whether anyone wants to listen to it! If you’ve made it this far, I guess you are at least partially interested.

I’d broadly decided (and apologies for the split infinitive, but it’s one of the things about the English language that really shouldn’t be wrong – how would Star Trek have sounded if Kirk wanted “to go boldly where no man has gone before”?) that I wanted to write about places I’d travelled to; things I’d seen and experienced. It was 29 years ago. Yet, much of the person I am today is attributable to that time in my life.

Getting there

I had been at my new unit, the British Army’s tactical electronic warfare unit for 5 months when a four month detachment to Sarajevo came up. I wasn’t actually on the shortlist to go. It was a Staff Sergeant’s posting and I was only a Sergeant. Yet, the fact that I wanted to go meant that I turned it into a short-list of one! You learn very quickly never to volunteer for anything in the Army – I was a slow learner!

Normally in the British Army, there is pre-deployment training. Nonetheless, due to the short notification period, none of this happened before my tour. It was difficult enough to pick up all my kit and get all my vaccinations completed. I also had to complete medical requirements and fill out all the paperwork, like signing wills. Additionally, I needed to get my rifle ready for transportation, never mind do any additional training.

I’d recently been part of a Divisional Skill at Arms march and shoot competition. I was fit and up to date with most of my training. At any rate, I felt prepared. Besides, I was getting out of “Sweaty Palm” an escape and evasion exercise that the Regiment carried out regularly, so that was an added bonus!

There were a total of 22 British Soldiers on this detachment, although not all came from the same parent unit. We were to be based in Sarajevo. This was in the French theatre of UN operations, though there were mainly French Foreign Legion Troops that we came across. However, our Electronic Warfare expertise was needed for the area. Sarajevo was one of the United Nations “Safe Areas”. Though as time would tell, a safe area didn’t really mean that much.

Before deploying, I met up with the Officer Commanding (OC) of the detachment. I’ll refer to him as “Captain A“. I also met with the Warrant Officer. I’ll refer to him as “Mac“. The three of us got to know each other over the course of the briefings. These included intelligence updates on warring faction activity. We also bonded over a few beers. We all got on well.

From the news, we observed that things were pretty active in Sarajevo. The intelligence updates we received confirmed this. Talking to the team who were currently in theatre further highlighted the activity level. We knew that it wasn’t going to be an easy tour. The guy I was replacing “Skelly” mentioned that they’d had a quiet start to their tour. However, things were becoming increasingly violent in and around the city. This violence was expected to continue. They had once been capable of freely move around the area. Now, they were actively targeted by the Bosnian Serb Army (BSA).

The OC and I were going out with the main deployment. We had to make sure that everyone had all of their administration sorted out. Mac would be following us out later, replacing Pat, who was presently the Warrant Officer in theatre. Little did Pat and some of the others know it, but the increasing hostilities were about to extend their tour somewhat!

I’d decided that as I was off to Bosnia, I wanted a telescopic sight on my rifle. The normal steel sights are pretty crap (a military technical term, meaning “not that good”). I quite fancied hitting whomever or whatever I was shooting at. The armourer happily provided me with one. Once in theatre, having such a sight on my weapon led to lots of interest in me at checkpoints. ABiH soldiers (Armija Bosnia i Herzegovina – the Bosnian Muslim Army) would gather round, nudging each other and whispering “Ah, sniper” while pointing at me. Little did they know that I was far from any such thing!

We had to get all the weapons packed and ready to go – even on military transports we weren’t allowed to carry our weapons with us. They had to go in the hold.

Once all of this administration was sorted, I took a couple of days leave, to spend a bit of time with Josanne, my wife, before deploying. I pulled together all the names and addresses of the folks I’d need to be writing to while I was out there (the more letters you write, the more you receive – and there’s nothing more demoralising to soldiers than not receiving mail while deployed. I suspect that with modern technology that is no longer the case, as you can probably Skype daily nowadays instead of writing letters). I still have the small black notebook that I was taking these notes in, which changes from lists of things to collect and all the team’s personal weapon numbers, to notes around the various warring factions and what they were up to, as well as my “to do” list for my intelligence reports. It seems strange to think how quickly my life changed based on the notes in this book.

And so it was that in the very early hours of 23 May 1995, I said farewell to Josanne as I left home for Sarajevo, via Brize Norton and Split, where I’d spent the next 4 months in a war zone that was totally surrounded by hostile forces with minimal to no support available if it was required. And I firmly believe that it’s that last point that made the tour such an interesting one, where resilience was critical to your wellbeing.

Background

Our unit was in Sarajevo to monitor what was taking place and to determine what was likely to happen next. My role was to take the raw information they provided and to try to work out what was going on.

I was deployed as the detachment analyst and Troop Staff Sergeant (I mentioned earlier that it was supposed to be a tour for someone the rank above me). We had a number of troops deployed in and around Sarajevo with varying intelligence related skillsets.

It is very rare that the type of work we were carrying out was used as a primary source of intelligence. More usually, it is used to back up existing information gained through other means, such as troops deployed on the ground. By the time I arrived in theatre, the Bosnian Serb Army (BSA), backed by Serbia, had stopped permitting United Nations (UN) troops free movement through any of their areas, so the work we were doing was turning into one of the only sources of information available. This hadn’t always been the case, and Skelly, who I was replacing, had numerous stories of the things that used to go on at the BSA checkpoints in the days when they could move about more freely and relations were more “cordial“.

Split to Sarajevo via Kisiljak and Malo Polje

We arrived in Split on 24 May and had to do all the usual things such as clear customs, get our passports stamped etc. I vividly recall being asked “Do you have anything dangerous in your luggage?” I’m still unsure whether or not he was being serious!

Both the current detachment commander (a captain) and Skelly were there to meet us. We collected all our gear and weapons. We also had to get across to the stores to pick up 120 rounds of ammunition and 2 ampules of morphine. We had to sign for these and keep them with us at all times. One of the things that is drummed into you in the army is that you never go anywhere without your rifle. On exercise, you even sleep with it in your sleeping bag, which is lovely in the middle of winter! I suppose that it’s at times like this that the reason for all the training seems obvious though.

We then headed for the exit, where we’d catch transport to the holding barracks in Split where we were scheduled to spend one night.

It took a couple of trips to get all our gear and us to the barracks, but we got there OK in the end. The OC was put up in the Officer’s Mess, and I opted to stay with the lads in what was termed “The Bubble”; a large plastic covered gym that got so hot during the mid-day sun that you could have turned it into a sauna. We were only supposed to be there for a night, so it wasn’t really any great hardship and it made more sense for me to remain with the others who would be making their way in to Sarajevo.

I caught up again with Skelly, an ex infantry Corporal who had transferred to the Intelligence Corps and worked up to Staff Sergeant. He briefed me on what had been going on in the last few days, saying that things were getting worse by the day in Sarajevo and that they were expecting more serious trouble soon. He had a few interesting stories to tell us about all the shelling that had taken place, including several aimed at the building we’d be living in. It all sounded pretty hair-raising stuff, but we were all looking forward to it for some reason.

Sarajevo had been a cosmopolitan city, inhabited by all three ethnicities from the Former Yugoslavia. Now, it was mainly Bosnian Muslim. It was surrounded by the Serbs, who also inhabited some areas on the outskirts of the city. We were in the same area as the Bosnian Muslims, although in places, the front line was very close indeed.

Skelly outlined that the Serbs had been firing more and more artillery into the city in the past few days, and that they’d had many near misses. It sounded like they got shot at just about every time they went down Sniper Alley, the infamous thoroughfare in the city, and I could already tell that I wouldn’t be forgetting the next 4 months in a hurry!

We were due to return to the airport the next morning to catch a Hercules from Split into Sarajevo. That was something I was particularly looking forward to. We’d all seen the news footage of the Hercules C-130 aircraft diving hard and fast into Sarajevo Airport. It looked great and I was looking forward to the thrill of riding that particular roller coaster.

Three days later though, the thrill still hadn’t eventuated. The Serbs had forced the closure of Sarajevo Airport. They had promised to shoot anything out of the sky that even attempted to fly close to the city, and the UN was taking them at their word. I think a couple of planes had gone up and had promptly been shot at, so my exciting flight into the city was off before it had begun.

The result of all this was that we had another few tedious days whilst trying to sort out alternative transport into Sarajevo. The heat of “The Bubble” caused me to regret not having chosen to sleep in the Sergeants’ Mess by now as we cooked by day and stayed almost as hot by night!

We eventually managed to hitch a ride with a Ghurkha transport convoy, which got us as far as the British Forces base at Kisiljak. From here, we arranged to get to a French base at a place called Malo Polje, where they held the ski jumping (think Eddie the Eagle) at the 1984 Winter Olympics.

To get our transport to Kisiljak, we had to get across to the Ghurkha barracks and left very early the next morning.

One of our Lance Corporals, a likeable chap, very intelligent, but probably not quite cut out for a tactical Electronic Warfare unit, decided to leave some of his kit, including his 120 rounds of ammunition and morphine at the side of the road. The first I knew of it was when he picked up my webbing and tried to put it on. When I pointed out (politely of course!) that he’d picked up my kit, he looked perplexed and said “well, where’s mine then?”

“Where did you have it last?” I asked him.

“I dunno, it was at the side of the road when we loaded all our gear onto the trucks”.

After a few expletives, a Ghurkha Corporal turned up in a Landrover. He’d followed us when he discovered the webbing lying at the side of the road. It was a lucky escape for a certain Lance Corporal!

The journey to Sarajevo

We had an early night and set off the next day along the coast with the Ghurkhas.

We headed south for the first couple of hours, where you’d never even have known a war was on. My wife’s family on her mother’s side originally came from the Makarska Riviera and some of them still lived there at the time. We actually drove past their village. It was completely unscathed, although I never had the chance to stop and say hello.

The trip as far as Kisiljak and then onto Malo Polje was fairly uneventful. As I mentioned, you wouldn’t have known a war was on most of the way. As we approached Mostar however, the Ghurka drivers became more tense and vigilant. At that point we put on our flak jackets and helmets and it was very noticeable that we had entered more hostile territory.

We spent, from memory, a couple of days in Kisiljak, which passed almost entirely uneventfully. All I can recall was us all being squeezed into a room too small to comfortably accommodate us while we awaited transportation to Sarajevo via Malo Polje.

The Infamous “Igman Run”

I’d been asked to pick up some beer at Kisiljak to take into the city as everyone was allowed a beer every now and then. Being Scottish, I bought a couple of crates of Tennents. Alas, we ended up drinking one of those with the French troops the night before heading in to Sarajevo. They fed us and gave us some wine, so we thought it only reasonable to return their hospitality with beer.

We drove, in a Saxon armoured vehicle, to the top of “the Igman Run”. Before setting off, the captain in charge of the detachment who had met us in Split gave us a briefing that went something along the lines of the following:

“The drive to the Igman Run is bumpy but uneventful. Just before we get to the top of the Run, we will stop. At that point we will radio the checkpoint at the bottom of the Run to ensure that nothing is coming up. This is a single-track dirt road, it is in full view of the Serbs and they will shell and mortar us on the way down. We will be moving fast. When we stop to do the radio check, you need to don your flak jackets and helmets. You also need to do your lap belts up tightly at that point.

The Serbs will usually aim for the front vehicle, trying to take it out. They do this because they can then hit everything behind it at their leisure. We are the front vehicle If we are hit, the vehicle behind us will not stop – it will push us out the way. If we are hit, get out of the vehicle quickly and take cover. Any questions?”

We had none – but I recall that it was a sobering briefing and announced our arrival proper into the war zone. I also don’t think the captain would have been much good at inspiring passenger confidence in an airline safety briefing!

The seats in a Saxon Armoured Personnel Carrier are set out as two benches on either side of the vehicle. I sat in the very back seat on the right hand side of the vehicle. The first that I knew about us being on the actual Igman Run was when my head started bouncing on the roof! On looking out of the rear window, I was now witnessing the shells / mortars / machine gun fire hitting the bank behind our vehicle.

It turns out that the captain had told an American officer at the front of the benches that we wouldn’t be stopping but that we’d done the radio check and were off. He was supposed to tell us to put our helmets and lap belts on. He didn’t. If anyone is at all interested, I can confirm that it’s exceptionally difficult putting a lap belt on and then donning your helmet when you are bouncing all over the place!!

We careered down the track until we reached safety. We got to the bottom and slowed down to go through the French checkpoint. We were now in Sarajevo, our first introduction to the Igman Run successfully completed.

The Captain told us all that we were due the driver several beers each, as his skill had kept us on the road during some of the most intense shelling he’d encountered on this tour.

I learned, a while after, that some of the shelling and mortaring had been so close that the Sergeant in charge of the Cymbeline detachment (a radar used to spot mortars, which was used by the Royal Artillery) had actually declared that we’d taken a direct hit.

This was the opening account in what led to me being called a “shit magnet”, as everywhere I went I managed to attract shit – in the form of mortars, being shelled or being sniped at. If I didn’t know better, I’d have taken it personally!

This was the one and only time I experienced shelling on the Igman Run, but Dave W, one of the Signals Sergeants experienced it several more times as he volunteered to provide top cover with the infantry to get supplies into the city. The vehicle he was in was hit on at least one occasion. I think he secretly enjoyed the thrill!

We also had to use the Igman Run each time we sent troops to and from our position on top of the mountain at Bjelasnica.

Sarajevo

Having completed the Igman Run, the remainder of the drive into Sarajevo was far more sedate, although it did take us very close to the front line in and around the airport.

When we got into our HQ in the TV2 building in Sarajevo, Captain A, who had been in the Saxon behind us, commented that he was very glad that they had focused all their fire on our vehicle as he’d discovered a couple of gas bottles in the vehicle he was in – one of which was leaking! He said that the shelling and tracer fire had made it a very interesting trip down for him as he manned the top machine gun.

As a sidebar to the Igman Run stories, one of the tasks we carried out in our time in theatre was to monitor the radio frequencies of the convoys coming down the mountain. On more than one occasion the Serbs succeeded in what they wanted to do – taking out convoys and preventing supplies from making it into the city. That made for harrowing listening. Interestingly, the Serbs didn’t usually fire at vehicles leaving the city via Mt Igman – even though they were going uphill and would have been much easier targets to hit due to their speed. Anything with UN on the side was definitely fair game to them. That much was evident even this early on. They clearly held the UN in contempt.

From our position at “Sierra Oscar” you could actually see Mount Igman in the distance. At night, they could even see the tracer fire and explosions:

When we’d left UK, Captain A had brought a hip flask with him. He had some port in it and had said “KB, this is for any of those “thank god for that moments” while we are in theatre. Hopefully we don’t have to drink it!” Having survived Day 1 in theatre, he promptly pulled it out and we both had a swig. I don’t think he’d intended needing it quite so soon! I also think that he could have done with a few bottles, never mind a hip flask! My love of port remains to this day, though thankfully it’s drunk purely for pleasure nowadays.

So having arrived in Sarajevo safely, we all set about getting our bearings. As we were moving into the building where those we replaced were still staying, there were no beds available for us. Once they moved on, we’d take their bed spaces.

I recall that either on the first night or one fairly early in our tour, we were all in the TV / Operations room one evening. Although there was only rarely electricity in Sarajevo, we had our own generator. We had Sky TV, a table football game and a bunch of paraphernalia “appropriated” from various places around Sarajevo (including a blow-up doll (named Doreen) hanging from the ceiling). Doreen was stolen from one of the Danish checkpoints. Soldiers tend to have kleptomaniac tendencies – and our predecessors in Sarajevo had clearly lived up to expectations.

Anyway, I digress. We were all stood around talking and some of the lads were playing table football. A firefight had broken out and we could also hear shelling and mortaring going on. It was initially in the distance, but was getting closer. Suddenly there was an almighty explosion that hit the back of the building (or the bank outside the building at any rate). The whole building shook. Everyone hit the deck apart from us newbies, who just stood there. Pat yelled at us to get down, and I think we got better at doing this without instruction as time went on!

My absolutely vivid memory of the first night in the city was of being the only person in the transit room. As the shelling went on, I tried to curl up behind my helmet and flak jacket to get to sleep. I had the worst night’s sleep ever. It didn’t take long to get used to it mind you, and I used to head off to sleep most nights listening to Bruce Springsteen at full volume on my Walkman.

Once Pat, Skelly and the others managed to get out of the city, I got to have a proper bed in the sergeant’s room. I was lucky enough to get the bedspace by the window, as at least you got fresh air that way. I did have some lovely sandbags next to me, not that they’d have done much good if we took a direct hit. Newbies started in this space and then worked up towards the door, however, being a lover of fresh air I stayed there for the duration.

UN Headquarters and my first experience of being mortared

The next night Tony McGarry and I took the Landrover down to the UN HQ. We were able to get a 10 minute call back to our family once a week. Some of the lads from the airport detachment had come in for the night and had been dropped off to make their calls. Tony and I went down to pick them up.

While we were sat outside in our white UN Landrover, the Serbs up on the hill started firing mortars. The first one landed fairly close and the second one closer still. They were clearly getting their aim in! I don’t know why but I picked up my rifle and ran towards the second explosion as soon as it happened. Tony was yelling “where the hell are you going“, at which point I turned back and got sheepishly into the vehicle. I have no idea to this day where I was going!

The Danish troops wouldn’t let us in the UN compound with our vehicle and clearly we couldn’t just leave it outside (I find it hard to imagine that although we were being actively targeted in the open, they did this. And worse still – being a Glasgow Rangers supporter, I was very fond of one of their nationals – Brian Laudrup – who played for us! But even my “Brian Laudrup‘ and thumbs-up signs were getting us nowhere! Due to this, I stayed with the vehicle and Tony went in to get the rest of the lads out, so that we could get back up to our building. In the same location a few days later, the Serbs were firing heavy machine guns up the street and Skelly had to get the vehicle off the road and wait for it to die down.

As things became more tense inside Sarajevo, the shelling was becoming more frequent. We were in the TV2 building and the TV1 building (in front of ours) housed some ABiH soldiers. For this reason, it regularly came under attack. I recall one direct hit that caused an almighty explosion that shook our building to the core. There were people killed in that, but fortunately none of them were British soldiers.

This explosion did make the news back home though, noting that the TV building had been hit and that people had been killed, so our families were all worried. We were told that they had all been told that we were all OK; however, when I spoke to Josanne a few days later, it transpired that this wasn’t the case. They all knew the building had been hit, but no one had been told that we were OK.

I suspect that this was one of the most worrying things for families. They could see what was going on in Sarajevo daily on the news, but the army wasn’t always very good at telling them how we were. I suspect that these days, Skype and the like would have removed a bunch of the problems that we encountered. Although it could also have caused additional ones. I had to explain away firefights a couple of times while I was on the phone, but with Skype, this could have happened far more frequently.

Sniper Alley

My role involved daily visits to the communications centre in the UN HQ. To do this I had to use Sniper Alley. Sniper Alley was a fairly long stretch of road where the Serbs held the ground to the right.

They were close enough to be able to fire at vehicles and people who used the street. Much of the war footage from the time shows areas of Sniper Alley, and it could vary from being fairly quiet to very active. We always had to go out with at least two people in each vehicle – equipped with rations etc, just in case we couldn’t get back.

There were French troops at the most active areas in armoured vehicles with 50 Calibre machine guns, but this didn’t seem to act as any sort of deterrent.

British troops have a tendency to wear berets rather than helmets where they can (this wasn’t the case with the French, who wore their helmets most of the time). Being less formal puts the locals at ease and seems less intimidating. We knew that the Sarajevans noticed this, because if we were ever wearing our helmets, they would ask us what was going on.

One day I was driving down Sniper Alley with Dave Rome in the passenger seat. We got part way down when we started getting shot at (loud ear-splitting cracks as the rounds passed over our vehicle). There was a very funny moment where we both reached for our helmets, laughing, at the same time and slipped them on! It wouldn’t have made any difference whatsoever, but I guess we seek security in the strangest ways.

We often played a trick on new people into the city. We had soft-skinned (i.e. not armoured) Landrovers and we’d have a bungee on the roof. Someone would be giving a run-down that we were now in Sniper Alley and to be alert for being sniped at. At that moment, someone in the back would pull the bungee down and release it so that it hit the roof. This would frighten the living daylights out of any of the new people, but was always good for a laugh. That was until someone got such a fright that they kicked the radio-set, short-circuiting it and filling the vehicle with smoke. Thankfully I wasn’t there for that one.

I did once complain to a REME Warrant Officer that the Landrover I drove pulled very hard to the right under hard breaking. I told him that this was especially so at high speeds. He asked what I meant by high speed. I told him that anything over 60mph was much worse. He asked what I was doing driving at that speed and I politely replied that he could do whatever speed he wanted down Sniper Alley, but I tended to do it with my foot to the floor.

Keeping Fit

Keeping fit is always topmost in soldiers’ minds. Even though we were in a war zone, we tried to stay fit. We had some weights that had been cobbled together with steel bars and concrete – fairly primitive but they worked. We also went out running in the local area quite a bit (although within our actual building compound).

This was stopped as the area became more and more active and I recall the OC calling Tony McGarry and me in as mortars started falling in the direct area one afternoon. I’ve no idea why he called us in –there was no way we were going to stay out there in that! I think it was the first time I was close to keeping up with Tony in a sprint to be honest! That day, you could actually see the mortars whistling over, they were so close to us.

Take a 500lb aircraft bomb and attach it to rockets…..

Army chefs are always at their best in the field. The food we ate in Sarajevo was outstanding and everyone always looked forward to mealtime. We’d just had lunch one day when Dave Rome and I were walking back up to our end of the building (where the TV and operations rooms were). Just as we got to the operations room, there was a whoosh overhead, followed by a crash, glass going everywhere and a loud thud (but no explosion).

We looked at each other and shrugged our shoulders in a “wonder what that was” sort of way. We went over to the window to have a look and at that very moment there was a huge explosion with shrapnel, smoke and debris going everywhere. It was a race between the OC (who had also gone to see what the noise was), Dave and me to see who could hit the deck first (I did mention that we got better at this over time didn’t I?).

I can clearly recall an old lady carrying two bags and wearing a bright red cardigan and a headscarf just as we’d looked out the window. She had been incredibly close to the explosion as we dived for cover. On getting up and looking out of the window, we saw her get up, dust herself down, pick up her bags and scurry off down the street.

Outside our building where the aircraft bomb hit

As the photo of that explosion demonstrates, it was a big one and if Bosnia had a National Lottery around that time, I’d have recommended that she bought a ticket. She has to be one of the luckiest people of all time. Look at how it threw the large metal wheelie bins aside.

The curious case of the defective mosquito net…

While I’ve already noted that I was really happy to have a bed by the window, it did have its disadvantages. These “disadvantages” were largely caused by Dave W and Mick B (one of the REME technicians with us). I used to work pretty late, pulling the final intelligence reports together once we’d finished the analysis of what had taken place during that day.

Being by the window, I’d very quickly decided that I needed a mosquito net. Fortunately, it was one of the things that I’d brought with me.

I used to vehemently complain and curse about how terrible my mosquito net was, much to the amusement of everyone else in the room. I used to have more mosquitos inside than there were outside. Dave later confessed that my cursing was so amusing that he would put the hand-held light over my bed and pull the mosquito net up for 15 minutes before they knew I was coming in. They’d then all laugh hysterically at my complaints about the aforementioned useless net! I was the only person with a mozzie net who had to liberally smear myself with the world’s smelliest repellent to sleep in it!

Humanity in adversity

In our compound we had some old Muslim ladies who were employed as cleaners and another Muslim man who pumped the fuel for our vehicles. This enabled the British Army to provide some of the locals with work. The bloke who pumped the fuel had a son who we called Sinbad (not sure what his name actually was, but it sounded similar to that, so it’s what we called him). Sinbad had been born in the war and knew nothing other than war. Unlike children from the West, he didn’t have a comfortable living and had few possessions and fewer home comforts.

We all used to get our wives and families to send gifts and sweets across that we could give to the local kids and Sinbad, as a result, was fairly spoilt. His eyes would light up when you gave him a packet of sweets and we’d always give him cans of Coke and Fanta if we could get hold of any. I remember giving him a couple of packs of sweets that Josanne had just sent across for him. He ran off with them and his dad tried giving me some carrots that he had been growing in his garden. I politely declined, but it was heartening to see someone who had nothing, trying to share with us what he had. It was nice to be able to help his family. I sincerely hope that they all live much happier lives now.

My driving skills prove to be not that good! (I definitely think that this should be said in a Jeremy Clarkson voice).

One of our positions very close to the front line was known as Sierra Oscar. It had been coming under increased attack from Serb artillery and mortars. The team at the detachment (at that time I think it was Dusty, Kenny S and some Canadians) had had a few close calls.

In one of these, the building and vehicles had taken a few direct hits (from which Dusty managed to get some shrapnel in his butt, of all places) and we made the decision to pull them out of that location until things calmed down again.

It was rather annoying that the team knew exactly who was shelling them (shown in the red arrow below) and we could even pinpoint their position. Captain A even went up the chain of command to the UN asking for air or artillery strikes to be called in on the Serbs, as they were clearly deliberately targeting UN elements. Not surprisingly, they said “no”, so our only option was to temporarily withdraw.

We took Ketts, as he was a tracked vehicle driver and we wanted to ensure that we could pull everyone out quickly. Alas, we didn’t even make it to the detachment!

On getting close to our position, the ABiH deliberately held us (in our white Landrover) on a hilltop in full view of the Serbs. We’d been there a while when the Serbs started to launch mortars at us. Rather like the time outside the UN HQ, they were getting their range in and they started getting closer (although I’d got out of the habit of running towards the explosions by this time!).

As it became clear that we were going to be hit fairly soon, the OC said “suggest you get us out of here pronto KB”. Ketts had been hanging out of the back door of the vehicle, keeping an eye on what was going on. I turned the vehicle around and started heading down the hill at a fair old pace. I’d just said to the OC that I’d slow down once we were around the corner and out of sight, when I swerved to miss a shell hole on the road and promptly careered into some poor Muslim’s vegetable patch at 60mph. It turns out that Landrovers do a decent job of ploughing!

In the melee, Ketts had caught his hand in the door and there was blood everywhere, not to mention a very bent looking finger! He still has the bent finger and now also lives in New Zealand. He reminds me every time I see him that I’m responsible for his deformity! I think that he has partially forgiven my not very good driving skills!

The incident led to me taking up smoking again – something that I’d given up years before. It was also very apparent that I truly was a shit magnet by this time!

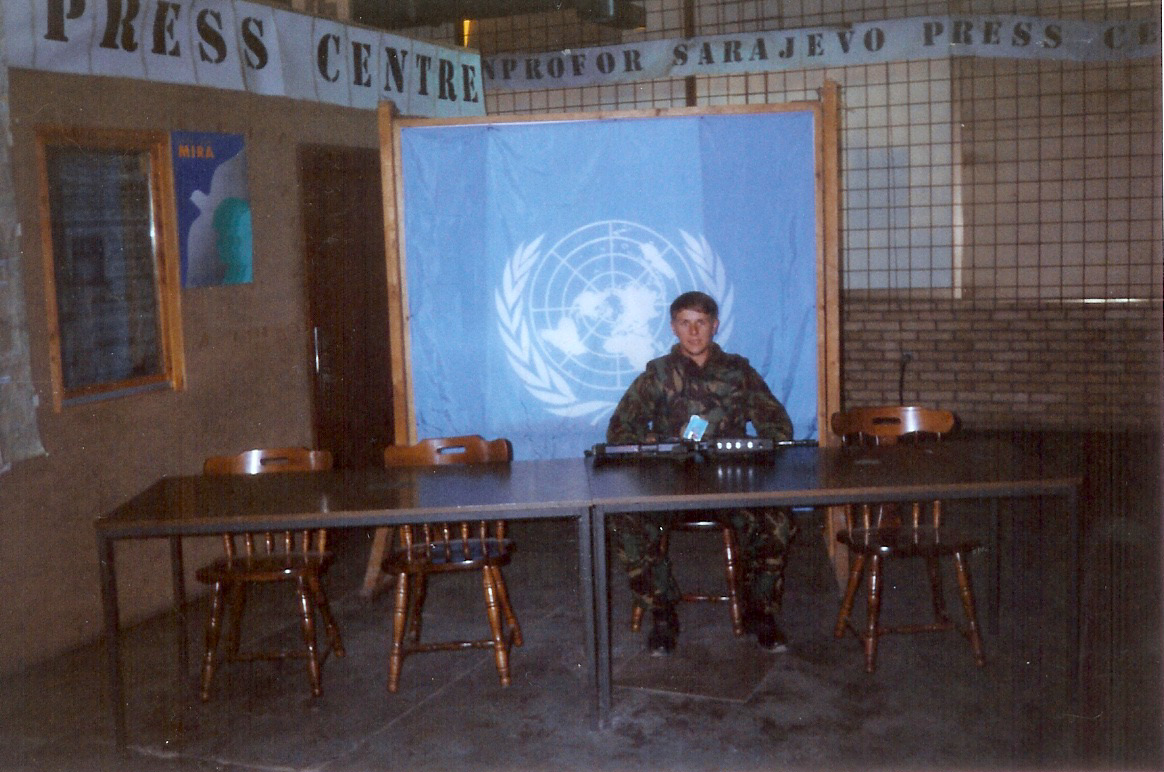

UN Press Briefings

Dave W and I used to attend the UN television briefings each day. To do that, we had to go up to the main Post Office building. It was always useful to keep up to date with what the UN said was going on and to compare that with the work that we were doing. Our briefings to them provided them with a fair amount of intelligence, but they obviously had people on the ground too by now, speaking to soldiers of both sides and trying to calm things down.

The UN briefing was just finishing and Dave and I were about to head outside. Dave pulled out his cigarettes and passed me one as we left. We hadn’t even lit them (and weren’t about to until we got outside), but a UN official came up to us and said “I hope you’re not going to light them – I don’t want to get cancer from breathing in that shit“. Quick as a flash, Dave looked at him and said “Mate, you’re in Sarajevo and you’re worried about dying of cancer? Seriously?“, as we walked off shaking our heads.

Smoking did turn out to be a bit of a blessing in a strange way. One of the roles I had to fulfil was working with the ABiH liaison officer, a Major, to ensure safe passage for our vehicles whenever we wanted to move them in and around Sarajevo (while under the auspices of the UN, we pretty much had to ask for permission to do most things. The process changed under NATO when we were back to doing what we wanted, when we wanted to, without asking for permission). However, the discussions at that time were always done cordially over a cigarette. I always had to ensure that I got my cigarettes out before the ABiH Major however – I’m not sure what they smoked in Bosnia, but boy, they were strong, smelly and tasted awful!

Getting caught on TV

Wherever you go in the world with the Army, there will be rules and regulations made up – usually for drinking games to catch people out. For example, it may be that you are only allowed to drink with your left hand at certain times, or else have a forfeit if you mess up. In Sarajevo, we had a rule that if you were caught on TV, you had to buy a slab of beer for the rest of the team.

This was taken so seriously that at one time, our vehicle mechanic, a guy named Billy, was caught on TV running for cover as our building came under fire. His life literally depended on it, but he was still fined a slab for getting caught on the telly!

Sarajevo Airport

Sometimes the people out at the airport detachment would stay there overnight. If we thought things were too active, we’d pull them in each night. This meant that they were at least in the same location as us if anything went wrong.

We’d often take the team out in a soft-skinned Landrover, but this became too dangerous, as not only were you too soft a target, but the local teenagers used to throw rocks at the vehicle all the time. I recall one occasion when we were having rocks thrown at us and Tony McGarry physically had to put his head down and just to continue driving to get us through.

Airport – houses had Serb snipers

When things were more active, we started to get people in and out of the airport using our 432 armoured vehicles. It was on just such an occasion that I was coming back from the airport. Dusty was driving and I was up top with the General Purpose Machine Gun (GPMG). There was a TV crew at the side of the road, no doubt looking for some extra footage to put into a news story.

No sooner had Dusty seen the crew there than he put the 432 into a big slide, causing them to scarper. I asked Dusty what he was doing and he pointed out that we’d be on the hook for a slab of beer and that was not about to happen!

I think that the team at the airport used to quite enjoy being there. The vehicle was situated behind a berm, providing a semblance of cover. There were snipers going in and out of the area where our detachment was however, and the teams knew which areas to avoid and you didn’t hang about when getting into the berm. It was also very noisy at night when the ABiH and BSA would take pot shots at one another.

If the team stayed at the airport overnight, it usually turned into an opportunity for them to go exploring later on. For example, there was a crashed Ilyushin aircraft on the runway and they used to regularly visit this to see what they could pilfer. Not that Ilyushin aircraft parts were of much use to us mind you! They were just collectable. In the same way that magpies are attracted to shiny things!

French Observation Post

While I spent most of my time in the TV2 building, a bunch of the lads spent time in various locations around it. These teams were very self-sufficient and were even closer to some of the fighting than I usually was. I recall Dags coming in one day telling me that one of the French Observation Posts that he’d been at by the front line had come under fire from a sniper. The sniper had been pretty good, as he had actually managed to shoot the binocular lens of one of the French soldiers. Another of those “buy a lottery ticket” moments.

Muslims attempt to break out of Sarajevo

We’d been seeing large troop movements of both Bosnians and Serbs on the lead-up to 16 June, an example of which was a large Serbian artillery unit had moved from Trnovo to the South of Sarajevo but by 16 June was in the city. We also knew that General Ratko Mladic was in and around Sarajevo far more frequently, so it was expected that Sarajevo was about to be the next supposedly UN protected enclave to be targeted by the Serbs (following the atrocities that had taken place in Zepa and Srebrenica).

The incessant crump, crump, crump of heavy artillery, the unremitting scream of the shells as they passed overhead, tank shells, mortars and staccato automatic gunfire was what awoke the city of Sarajevo at 3am on the morning of Friday 16 June. The enormity of this particular bombardment would have ensured that even the deaf would have struggled not to notice that something was going on, and I’d imagine that there would have been very few who slept through such a cacophony.

Sarajevo had become sadly used to mornings such as these, but this particular one was a step up from the norm. It was as surreal an experience as I’ve ever known. Both frightening and exhilarating at the same time, I almost had to pinch myself to determine that I hadn’t been transported to the scene of an epic Hollywood war movie. Sarajevo, the once beautiful city that had hosted the Winter Olympics in 1984, was kicking off yet again.

If you’ve read this blog from the start, you’ll know it wasn’t my first experience of being under fire in Bosnia and it wouldn’t be my last either. It was, however, sufficiently memorable that the feelings associated with that day have remained with me still. If I stop and think about that day, about all that went on, I can almost feel and smell myself back in Sarajevo. It’s a reminder of how a destructive war tore a country apart, pitting those who were once friends and neighbours against one another.

The level and intensity of the activity suggested that something out of the ordinary was taking place. And we were smack, bang in the middle of it.

The events of that morning had been brought about by the Bosnians trying to create a corridor to break out of Sarajevo. The Serbs had decided that this was not in their interest and set about stopping it. The shelling – some of the most intense noted around Sarajevo throughout the Bosnian war – kicked off at 3am and lasted until almost midnight that day. By that time, the Bosnian Army, realising it had failed in its attempt, fell back to their earlier positions and awaited the next opportunity to try to free their starved and beleaguered city.

The BSA was numerically inferior to the ABiH, but what they lacked in personnel, they more than made up for in equipment. With around 96,000 troops, their presence was felt through the artillery, tanks and other heavy equipment that the ABiH would have given their right arms for. For their part, the ABiH had around 188,000 troops, but they were an out and out infantry army with few heavy weapons. On the outskirts of Sarajevo, the Muslims were still operating in trenches – a real kickback to the First World War. The composition of these opposing sides led to many stalemates, interspersed with copious shelling, mortaring and small arms fire. Things were never quite as they appeared and the situation changed quickly, frequently and without warning.

It was thought, at the time, that the Serbian forces had around 800 artillery pieces in and around Sarajevo. On that fateful morning, it was easy to believe that they had pointed most of these into the city, had stood back and had lit the blue touch paper. They were mainly dug-in, giving them a greater degree of protection, but the downside of this for the Serbs was that they could not quickly change targets. This didn’t really matter, as their target, Sarajevo, wasn’t moving anywhere. The Serbs did have self-propelled artillery (such as the Russian 122mm “2S1” howitzer), and much of this had been operating to the south of the city for a period of time.

The shells rained down like a squally and brutal summer downpour for most of the day (I hate to think how much all that ordnance would have cost – certainly enough to feed all of Sarajevo’s starving inhabitants!) and the noise and explosions were something the likes of which I’d never experienced before. It may have seemed like overkill, but it was a typical Serbian response to a numerically superior enemy force trying to break out of the city. The Muslims in Sarajevo had been under siege for months with only two ways into and out of the city. One was the perilous route over Mount Igman, with the other route being via a tunnel created close to Sarajevo airport.

As I mentioned earlier, the ABiH had been building up to this offensive for weeks, pulling in troops from other areas around the city, seeking a way out of their current predicament of enforced incarceration.

Correspondingly, the Serbs had also been gathering their forces and more importantly, their hardware, around the city. While they had insufficient troop numbers to take the city using their infantry (far greater numbers would be required to clear the city in the street to street fighting that would ensue under such a strategy), I suspect that they wanted to ensure that a breakout was impossible. It was clear at the time that Sarajevo, like previous UN safe areas such as Srebrenica, was a target for Milosovic and his troops.

As the day’s shelling continued, myself and the OC had been working out of our Ops room on the second floor of the TV2 building, however, we’d ensured that those not required were down in the cellar. If the building took a direct hit, we would minimise casualties in this way.

For me, and I’m sure for the OC, as well as the troops out in the detachments, it was an utterly exhausting day as we went through the huge amount of warring faction activity. There were several times during that day when you could hear artillery barrages coming closer and closer, yet we both knew that there was absolutely nothing we could do about it. I’ve never been so busy in all my life and could see the situation changing by the minute as each side took the ascendency across various locations.

Several of the buildings in our area took direct hits that day. I can still recall my amazement at discovering that shells and mortars actually did sound, in real life, as they sounded in the movies! The high-pitched scream was exactly the noise that you heard as the shells roared in from what could have been almost any area surrounding the city.

At the end of the day, once the shelling started to subside, I think we were all utterly exhausted. I know I felt like I’d been up for days and would have killed for a hot shower, a beer and an early night. Alas, all three were in incredibly short supply in Sarajevo!

Incident at the Old Fort

There is another incident that is lodged firmly in my memory. We had a couple of our team in a detachment up at an area in Sarajevo called the Old Fort. This was in a Muslim area and was generally safe, but it had been coming under a bit of artillery and small arms fire. We decided we should relocate them to another area of the city for a while and myself and the OC went up to resupply their rations and to tell them that we were planning moving them out, for a few days at least. It had never been problematic for us to get into this location before.

On this day, we headed up to the Old Fort, but one of the Bosnian soldiers in the area was adamant that we couldn’t get in to the detachment. The OC was as adamant that the ABiH were in no position to stop us and got out of the vehicle to go and speak to the ABiH officer. Around 30 seconds later, Captain A came back around the corner, hands above his head, with the same ABiH soldier pointing his rifle directly at him. As I was driving the vehicle (I’m amazed anyone let me following my earlier driving incident!), my rifle was stowed next to me in a rack. As I reached towards it to unclip it, the guy swung his rifle directly towards me. I swear that it’s the closest I’ve ever been to involuntarily emptying my bladder! I don’t doubt for a moment that he would have fired. The OC got back in the vehicle and said “KB, I suggest we get out of here“. And we did. Some high-level negotiations took place after that, enabling us to get back in to remove our people from that location.

The beginning of the end

On 28 August, the Serbs sent mortars into the old market in Sarajevo, killing 43 and injuring over 70 civilians. This was not the first of these events, as in February 1994, a similar occurrence killed 68 and injured 144. This one act signified the beginning of the end, as NATO, having had enough of the inactivity of the UN, decided that they would take control of the war and put pressure on the Serbs in order to obtain a ceasefire.

A NATO multi-national Brigade (MNB), also referred to as the Rapid Reaction Force (RRF) that included French and British Troops started gathering on Mount Igman and NATO aircraft (most of which were US) were sent closer to the area. It was rumoured that the MNB was going to fight its way into the city, up a route controlled entirely by the Serbs. To do this, it was going to have artillery and air support. We were in close liaison with the MNB (and I was sending them daily situation reports (Sitreps)), keeping them up to date with the warring faction activity in the area.

It was around this time that Fiona F, another analyst sergeant came into Sarajevo, doubling our analytical capability. This was very handy, given that there was so much going on at the time that there was too much work for just one person.

There had been numerous atrocities committed, not least of which was the massacre of Muslim males in Srebrenica. I suspect that NATO was losing whatever faith they’d had in the UN long before the mortaring, but it seemed that this solitary act of terror forced their hand. Furthermore, we knew that there had been additional movement of Serb troops heading towards the city.

One of my Sitreps to the MNB accidentally caused a bit of panic. I’d pointed out that the MNB was now within range of self-proppelled artillery elements that were around Sarajevo. I think this was read as they were about to come under attack. I had to reassure them that they had actually been within range for quite some time, but that they seemed to have other things on their mind at the moment!

The night before the NATO operation began we were obviously on a high state of alert and were aware of where certain elements were located and what they appeared to be doing. Our work became more important after the air strikes and artillery barrages, as we could help ascertain the effectiveness of NATO’s strikes, along with any observations on what we believed had been successful and what hadn’t.

There were multiple waves of attacks from French and British artillery on Mt Igman, followed by air strikes from various NATO forces. The following report by Martin Bell gives a decent overview of how the NATO operation began, and it’s worth watching the first few minutes:

Martin Bell news item from when NATO took over

While the Serbs initial response was to continue firing shells and mortars into Sarajevo, further NATO action meant that this soon ceased. It started to have a significant impact on their troops and the people of Sarajevo seemed to give an audible sigh of relief.

The NATO operation started paying dividends fairly quickly and shelling in and around the city diminished. This enabled more visitors to get into the City to see first-hand what was going on and the impacts of the war. We had a Brigadier coming in for a briefing and he was escorted by a Lt Colonel who used to be my Officer Commanding at a previous Regiment (Colonel N). I went through my briefing, outlined what had been going on etc and when I was finished I asked if there were any questions. The Brigadier had a few which I answered. Colonel N then turned to me and said “Thanks Sgt Blyth, no questions, but I’d like to point out that I think that’s the first time I’ve seen you sober“.

The aftermath

Things in the city quietened down considerably after the NATO intervention and at the end of September, we all managed to leave Sarajevo and return to our families on time, being replaced by those on the next tour. While our tour had been frantic and at times manic, the focus of theirs would be slightly different but just as important. Having spent summer in our building with no electricity, I’m also fairly certain that it would have been exceptionally cold in the winter. I didn’t envy them that!

My last real memory of the detachment was of getting a flight in a Russian Antonov from Sarajevo to Split (the airport was open and there was free movement in the sky and on the ground again). It felt like it took forever to get off the ground and I seriously wondered if it was going to run out of runway. It took off and our short flight to Split was entirely uneventful. On getting off the aircraft however, a Russian airman was pouring bottles of cold water all over the wheels and there was steam everywhere. The flight was going on elsewhere having dropped us off. I was glad that I wasn’t going to be on it!

Coming home

Coming home from this detachment was actually difficult. To come from a theatre of war and get back to normality took quite a bit of getting used to and winding down took some time. I could hear the eerie wail of the sirens that went off regularly in Sarajevo just before bombardments began, could see the people scurrying for cover and relived some of the incidents over and over again.

At the start, I didn’t speak about it much. It was always there in the back of my mind and it probably took me quite a while before I started getting a good night’s sleep. I didn’t have nightmares or anything – I just couldn’t get off to sleep very easily. Then one day I decided to open up and talk to Josanne about what had happened. She had seen the news, saw what was going on and there were even a couple of times when I was on the phone to her when we started getting shelled, or people opened up with machine guns, so I couldn’t very well pretend that nothing had happened. There was also the incident when our building was hit and no-one was told that we were all OK. Josanne understood and provided her ear. I genuinely think that it was opening up and talking about it that then made it easier to move on.

We were offered counselling when we came back. I have no idea if anyone took the offer up or not. I didn’t. I didn’t think I needed to and as I mentioned, once I spoke to Josanne about it, it seemed to clear it out of my mind and I could get on with my life as normal again. If there is one piece of advice I can give to anyone who has returned from an event such as this, it would be to make sure that you talk about it and don’t bottle it up – there is nothing wrong with reaching out for help; nothing to be ashamed of.

Reflections 22 years on

I maintain to this day, that most people who join the Army want to see active service. I also believe that I served in one of the best trained (if not best equipped) armies of the world (although I’m also certain that most people will say that of whatever army they served in). It’s only natural that young males, oozing testosterone want to pit themselves against foes to see how they compare. We all think we’re the best. We all think we’re invincible. Most even think God is on their side. I think that the God on our side bit is the absolute folly that results in religion causing so many wars.

I know that since getting out, a number of my friends have seen several campaigns and it seems almost that as soon as one ends, another one blows up somewhere else in the world. People these days do several tours of Bosnia, Iraq, and Afghanistan – the list goes on. I don’t envy them and am thankful that none of my close friends have been killed. A number of people from the Electronic Warfare unit where I served have been less fortunate over the years and I dare say that they and their families would gladly have foregone the active service with hindsight. My thoughts go out to those families.

There is undoubtedly a close bond among military people that remains long after they have served together. Those days I spent in the Army created some life-long friends and although I now live on the other side of the world, I still regularly keep in touch with a group of those I served with.

Although I was never your army-barmy type of guy I’m not too different to everyone else. The lure of the Army was the opportunity to get away from home, to see different places, to have fun, to earn money and to buy myself some thinking time around what I wanted to do with myself. Oh yes, and I think there may have been a bit of drinking in there – that usually got me into trouble in some form!

The war in Bosnia seems to have been like so many before it. Unnecessary. It was a war over religion, land, perceived differences and way too much focus on those perceived differences. Thousands died as a result – some in horrific war crimes, others in fighting, still others innocently while trying to eke out an existence in their war-torn country. But it was all unnecessary. The action of NATO put a stop to the war continuing, but things will never be like they were before. And there are many who aren’t around to appreciate it.

I like to think that the role I played, that my comrades played and that the British Army played helped people to eventually live better lives. I know that there are those who think that we should stay out of the fights of others. I dare say that the inhabitants of places such as Sarajevo, Pale, or Srebrenica would have been far happier not to have been left at the behest of Karadzic, Mladic or any of the other power brokers of this war. And from that perspective, I believe that you can’t turn a blind eye to the plight of others.

Benjamin Disraeli once said, “Most people die with their music still locked inside them”. There were many in Bosnia who died long before they had the chance to unlock theirs. I feel all the better for getting mine out there – so thanks for taking the time to “listen”. I hope it’s been worth it.

Thankyou Kev for putting our experiences in words.

Cheers mate!

LikeLike

I hope I remembered most of it fairly accurately after all these years! 😊

LikeLike

An interesting read mate – brings back a lot of memories – i think i did 6 tours all told with the first being the best – good stuff

LikeLiked by 1 person

6 tours is a fair old whack to have done out there! Hope some of those medals were nicer than the UN one! 😊

LikeLike

Kev, fantastic account of what was probably the best and worst tour I ever served on. I went back out to Sarajevo in 2008 and it has changed a lot but a lot of the damge especially around the airport has been left perhaps as a reminder of how Sarajevo suffered.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’ve often said to Josanne that I’d love to go back and see how it looks now. It was a crazy place to be back in 1995, but a place where we needed to be.

LikeLike

640 Reunion at the Holiday Inn???

LikeLiked by 1 person

Haha. Be a bit more expensive than last time I reckon! 😁

LikeLike

What a fantastic read. I’m proud of you cousin x

LikeLike

Cheers Darren. 😊

LikeLike

Great read Kev, brought back a lot of memories, different tour but same places.

LikeLike

Cheers Jock. You were on the same tour as Skelly and Pat weren’t you? 😊

LikeLike

Well written mate, thanks for sharing

LikeLike

Cheers for that! Had to leave a bunch out for all the obvious reasons! 😁 Glad you enjoyed it.

LikeLike

Thanks for sharing Kev – I really enjoyed it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Cheers Kath. Glad it didn’t send you to sleep! 😁

LikeLike

Great read, brought back some memories

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m sure there’s a decent few stories you could add to it! 😊

LikeLike

Cracking read mate. Brought back lots of memories

LikeLiked by 1 person

It was definitely an interesting time! I’d always wanted to write about it so thought the easiest way to do it was in this way 😊

LikeLike

PS. Hope you’re well mate! 😊

LikeLike

Fantastic read I was immersed…heart felt sympathy for civilians…glad your able to express yourself so well it grabbed me …thank you

LikeLike

Thanks for taking the time to respond Steve – and glad you enjoyed it. It was certainly an interesting time of my life when I saw both the best and the worst of human behaviour! We were lucky in that it wasn’t our country, our homes, our people.

LikeLike

Hi Mate, I’ve just read this again as a refresh, if we put all our stories together about those 4 months it would make a pretty decent book. Many memories, none forgotten

LikeLiked by 1 person

It definitely would. So much happened there in such a short period of time.

LikeLike

Hi Kev. I finally got around to reading this over the weekend and really enjoyed it. Very well written. Starting to plan a trip back in 2020 (probably in September) for 25th reunion. Starting in Split and driving to Sarajevo. Three of us are up for it so far. Once I have a firm date will post on 640 fb group. Cheers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

That will be a fantastic trip. I’d love to see how the place looks now!

LikeLike

Hi Kev. Finally got around to reading this over the weekend. Really enjoyed it and well written. Starting to plan a trip back in 2020 (probably in September) for a 25th reunion. Three of us are up for it so far. Once I have a firm date will post on 640 fb group. Cheers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Hello Kevin,

thanks for such real description of a soldier’s life back in Bosnian War. It’s wonderfully written and just so interesting. I just wonder, maybe do you or your colleagues have more photos or stories of the Olympic venues from the time? I would appreciate that!

LikeLike

Thanks for your note Mirko. I think the ones I have are in here, the ski jumps at Malo Polje and the start of the ski run on Mount Igman. I may have one from a distance of the ice rink in Sarajevo (where part of the roof has collapsed). If you flick me your email, I can send that on to you.

Regards

Kevin

LikeLike

Thank you for recording that. I had two tours in TV2. It was the most interesting and heartbreaking time of my service career.

LikeLike

Yes, it was definitely both of those. The best and the worst of folk in one location. Thanks for reading it and taking the time to comment. I’d love to go back and see what it looks like now.

LikeLike

I’ve got some Sarayevo images that may interest you. Where should I send them?

David

LikeLike

Hi David, that sounds good. Flick them through to Kevin.blyth@yahoo.com 😊

Cheers

Kevin

LikeLike

Asleep !! That is the only picture you could find 😳

I have sent you some pictures from a recent trip will send some more when I go back in July (a lot warmer) Holiday Inn is now Holiday Hotel (lost the chain) Sniper alley is a lot easier to navigate now especially walking.

still apart from the picture a good account of a busy couple of months.

LikeLike

Great read Kevin 👍🏼

LikeLike

Cheers Katy. Definitely one of the most interesting periods of my life! 😁

LikeLike

Fantastic read Kevin > the woman who dusted herself off coming back from the shops as a bomb lands, that must stay with you. A wild drive in with a old Russian-style Antonov home, and not a moment of peace in the months between.

LikeLike

Thanks Chris – yes, there’s a fair bit of it that stays with you. I always consider myself fortunate to have experienced this but not in the same way as the locals who had no option other than enduring it. Certainly shows you both the best and the worst of humankind.

LikeLike